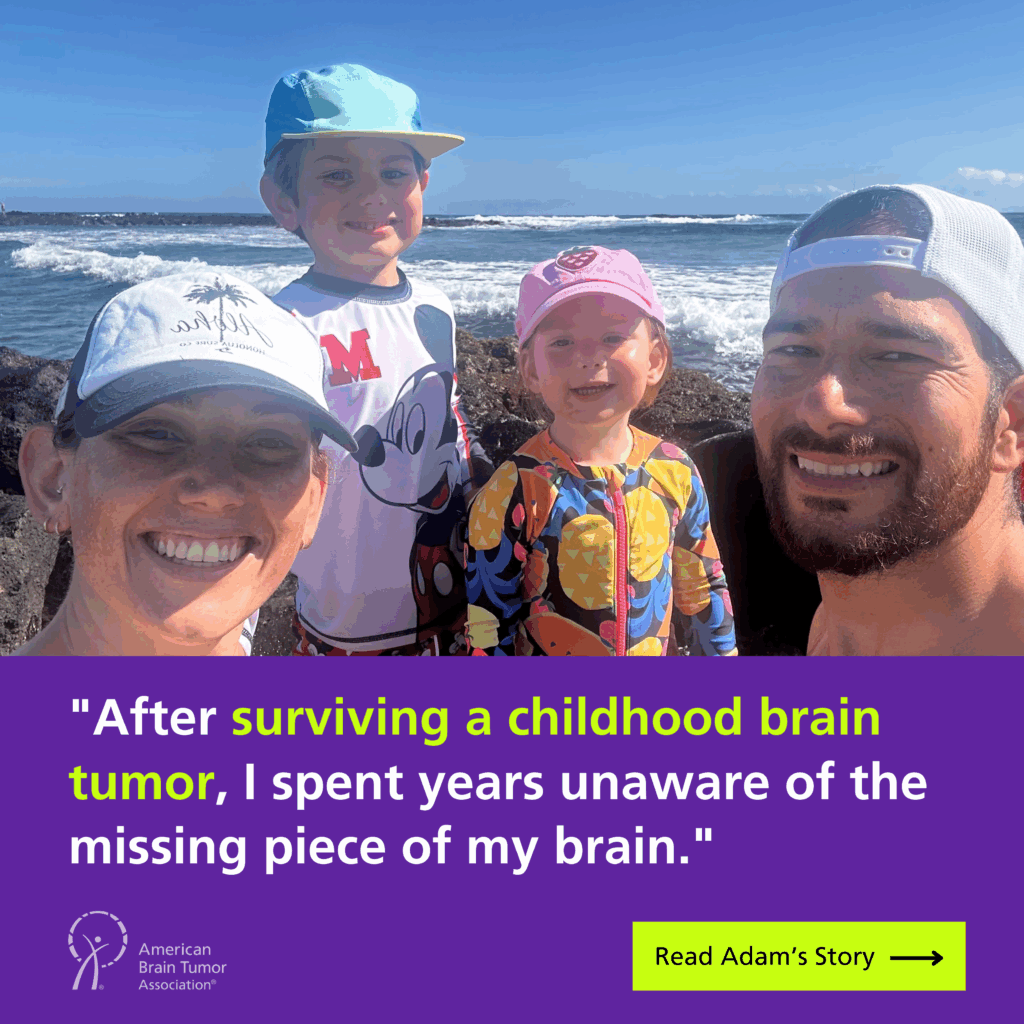

by Adam Bunnell

When I was a child, I was diagnosed with a glioma near the fourth ventricle of my brain, adjacent to the cerebellum.

The tumor was surgically removed, and shortly after, I developed bacterial meningitis—a severe infection that compounded the trauma my young brain had already endured. My family was informed about the tumor and the risk of complications, but we were never told that a portion of my cerebellum had been removed.

For most of my life, I had no idea that this part of my brain was missing.

Growing up, I always sensed that something was different about how I processed the world. Verbal instructions were often hard to retain, and fast-paced conversations or new information could feel overwhelming. But like many people with invisible disabilities, I pushed through, adapted, and found my own strategies to cope.

I succeeded academically, built a career in healthcare analytics, and even taught a healthcare statistics course for an academic health system in California.

It wasn’t until my mid-thirties, after I requested a new brain MRI due to ongoing neurological concerns, that the truth finally emerged. A neurologist explained something that had never been revealed to me: I was missing a portion of my cerebellum, likely due to the childhood tumor resection. This news was both validating and deeply emotional.

For years, I had struggled with cognitive differences, and now I knew they were real, physical, and measurable.

Following further testing, I was diagnosed with a mild neurocognitive disorder, likely stemming from the trauma of the surgery and the meningitis. This revelation changed how I see myself and my past.

Many moments in my life—like struggling to retain spoken information, needing visual aids to process complex material, or feeling mentally exhausted after intense conversations—suddenly made sense. What I once saw as personal shortcomings, I now understand as natural consequences of a brain that has endured more than most people realize.

In many ways, I’ve been lucky.

I’ve built a fulfilling career in healthcare policy and analytics, helping improve care delivery systems over the past 15 years. I’m a father to two young children and an Iron-distance triathlete. Interestingly, endurance sports—especially long outdoor runs and rides—have played a significant role in my recovery and resilience.

Physical activity has helped regulate my nervous system and improve how I process external stimuli in ways that science is only beginning to understand. I often wonder how much of my cognitive adaptation has been shaped by movement and exercise, even without me realizing it.

What troubles me most, however, is not my neurological differences, but the fact that I had to uncover them on my own. After the surgery, there was no follow-up. No one connected the dots between my childhood trauma and the challenges I would face in adulthood. For decades, I managed a complex neurological condition without guidance, accommodations, or even recognition that something deeper might be going on.

My story is one of late-discovered survivorship.

It’s about falling through the cracks—not because people didn’t care, but because systems weren’t built to track pediatric patients into adulthood. It’s also about how invisible conditions are often misunderstood, minimized, or missed entirely, even in medical settings.

By sharing my story, I hope to give a voice to others who have lived for years without answers. I hope to encourage better continuity of care for pediatric brain tumor survivors and advocate for long-term neurological follow-up as a standard, not an exception. If my experience prompts just one doctor to revisit an old chart, or one adult survivor to ask for a second scan, then sharing my journey will have made a difference.